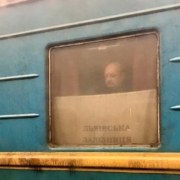

Sometimes when I’m feeling dark, I pretend I am a Russian “political technologist” designing influence operations in Ukraine. I try to deconstruct what Russia is trying to achieve and why. I scratch my head. Do they know their efforts to undermine Ukrainians’ commitment to defending themselves is dumb and ineffective? Do they do any research at all?

Russians have had little success in undermining Ukrainians’ support for the war effort or their leaders. Pre-full scale invasion, however, Russians were pretty good at causing division in Ukrainian politics, particularly around major strategic issues like EU and NATO membership. Russia used its television channels, Ukrainian political allies and Ukraine’s natural political divisions to prevent leaders from building consensus about Ukraine’s future direction. For a number of reasons, it has become much harder lately for Russia to get traction.

Four Major Changes in Ukraine

I can identify four major changes in the Ukrainian information environment to help explain why. These are important for anyone trying to understand Ukrainian public opinion since the full-scale invasion.

- Ukraine blocked Russian TV channels from Russia in 2014 and shut down Russian-language channels in Ukraine owned by Russian-aligned oligarchs in 2021.

- Ukraine banned 11 Russian-backed political parties in March 2022.

- Ukrainians are sophisticated information consumers.

- Ukrainians are not receptive to and/or are openly hostile toward messaging they perceive as coming from Russia.

No more Russian TV channels

Television remains the most effective tool to shape mass public opinion. Accordingly, the single most important factor limiting Russian influence over public opinion in Ukraine has been the closure of Russian channels from Russia and Russian channels from Ukraine. Kremlin narratives and coordinated messages simply do not reach a mass audience in Ukraine like they used to. (Ukraine’s United TV Marathon has succeeded, to some degree, in achieving this. That’s a different post).

Sure, Russia has access to Telegram. Everyone does. Telegram channels are useful for delivering targeted messages to receptive audiences who are looking to confirm their biases, who distrust official narratives or who want to fill information gaps. All kinds of channels fill this space, however, making it quite fragmented and noisy. Russia holds no particular advantage, like it did when Kremlin-friendly TV stations pumped garbage 24/7 into millions of Ukrainian living rooms, unchallenged.

Russia-backed political parties shut down

Ukraine’s democratic institutions provided cover for Russian-backed political parties and their parliamentary faction, allowing them to undermine democracy from within for years. The largest, Opposition Platform/For Life, enjoyed legitimate support from voters in Ukraine’s East and South and held 44 seats in the Rada. However, it was backed by Viktor Medvedchuk, a pro-Moscow Ukrainian oligarch with close ties to Putin. Banning these parties, while controversial, inhibited Russia’s ability to take advantage of Ukraine’s democratic system to promote the Kremlin’s agenda.

Ukrainians are sophisticated information consumers

Ukrainians have become sophisticated information consumers, a process that predates the full-scale invasion. Going back to at least 2016, Ukrainian civil society and educational institutions developed tools to help Ukrainians identify information sources designed to manipulate them. Some approaches worked, some didn’t. Some Ukrainians will never be reached and will remain vulnerable to, or even embrace, Russian influence. Many more, however, learned to pay close attention to who might be fighting for their attention and why.

Most Ukrainians now consume information primarily in Ukrainian, either via Telegram channels or United TV Marathon. They can identify Russia-friendly channels and commenting bots by their bad grammar and spelling as easily as native English speakers can spot Russicisms. Ukrainians also know that Telegram channels are the main source of unproven, manipulative information. They say they read with caution and double check against other sources, evidence of their information resilience.

Most Ukrainians are deeply hostile toward Russia and its narratives

Pre-full scale invasion, a substantial number of Ukrainians used to hold, if not positive attitudes toward Russia, at least neutral views, particularly in the East and South. No longer. I suppose Russia can count that as an accomplishment of sort. No one else – certainly not the West — could have turned so many Ukrainians against it so thoroughly and most likely, irreversibly.

Ukrainians swat down messages they suspect might be coming from Russia, including common imperialist tropes that few questioned. Not only are Ukrainians generally not receptive, but the narratives often infuriate them. That’s not fertile ground for your influence operation to take root.

Most importantly, Russians not only lack the tools to influence Ukrainians’ opinions, they lack an understanding of their audience. Russians are trying – and failing — to undermine Ukrainians’ faith in a democratic system in which most Russians cannot perceive value. If they could relate to the importance of independence to Ukrainians and the complex relationship Ukrainians have with their democratically elected leaders, Russians might rethink their approach. The enormous gap between Russia’s and Ukraine’s worldviews makes it difficult for Russians to understand post full-scale invasion Ukrainians well enough to create anything but the clumsiest narratives.

May Russia continue to fail

None of this is to say that influence operations can’t work to undermine Ukrainians’ support for the war effort, build resentment toward their leaders and sow divisions in society. I’ve also thought a great deal about how that can be done. Russia, however, isn’t doing a very good job at it. Let’s hope they keep it up.

Christine Quirk is a France-based opinion research consultant and strategist who has been managing strategic qualitative and quantitative research projects in Ukraine since 2006 for a variety of clients. She has observed hundreds of focus groups on topics such as Ukrainians’ view of the full-scale invasion, elections and the political environment, how Russian influence operations shape Ukrainian public opinion, LGBTQI rights, women’s political participation and many others. Contact Quirk Global Strategies for more information about our work.