2020 has been something else, hasn’t it? It’s been discouraging trying to run every project from home — even from the Côte d’Azur. I’ve built my business on my ability to engage personally with people, and the environments that shape their opinions. Without this interaction, I feel like I’ve lost one of the most important tools I use to design insightful research. Couple that with the challenges presented by a near-complete shutdown in quantitative and qualitative data collection in many countries, it’s a challenging time to be a pollster.

Everyone knows lots of things aren’t working. But let’s take a look at what is. The transition to CATI interviewing in some places, sped up by COVID, is a genuine bright spot.

CATI Phone Surveys

If you have survey projects in Western Europe or North America, you’re in great shape. Other than slower turnaround times and increased technical demands placed on data collectors, phone interviewing continues using CATI (Computer-Assisted Telephone Interviewing) Strategic questions about whether it’s a good idea to poll in such an unpredictable environment remain but there aren’t health concerns or technical barriers to worry about.

It’s more complicated for my clients. I work in low- and middle-income countries where interviewers administer general population surveys face-to-face (F2F). It’s the only way to sample rural, poorer or older populations. COVID ended this type of data collection overnight almost everywhere. Even though the main tool I use to conduct surveys disappeared, my need to understand public opinion did not. Responsible field firms have scrambled to figure out how to stay afloat and design alternative means to get the work done safely.

During the dark depths of France’s total lockdown I spent a lot of time on helpful ESOMAR and WAPOR webinars. Designed to help research professionals figure out how to operate in this new environment, the seminars brought together data collectors from around the world to talk about what was working and what was not.

There was plenty of bad news. Low and poorly-distributed mobile telephone penetration in parts of Africa, Eurasia and Latin America means that nationally representative samples aren’t possible for now in lots of countries.

But some vendors highlighted the progress they’ve made in the transition to CATI in countries where mobile penetration has been growing to the point random sampling is becoming practical. Accordingly, the Big Kids, which include certain departments of USG, Pew and Gallup — are driving the transition. They have been helping local data collectors build technical capacity. improve quality control and retrain interviewers. This benefits the small fish like me. Thanks guys!

Case Study: India Makes the CATI Transition

Over the past 10 years I have fielded multiple F2F surveys in India. Because of its geographic and demographic complexity, it had always been one of the most difficult countries to randomly sample with anything but a gold-plated budget. Clients with normal budgets have to accept trade-offs during sample design. With a survey scheduled to field in mid-March, my client and I had already come to terms with those trade-offs. I designed a sample that balanced the goals of the research with the confines of budget and time using F2F. Sadly, COVID lockdowns pushed the survey into data collection purgatory, unlikely be released unless I found an alternative to F2F.

Since I last fielded an India survey a few years ago, CATI has become a viable data collection option. Thanks to my Zooming, I learned that mobile penetration is 90%. The darkness of French lockdown lightened.

With the client’s consent, I prepped the survey to switch modes. Most significantly, we translated it into 11 languages, compared with the four or five I’d used in previous face-to-face surveys, which sampled fewer states. After translation backchecks (all of them!) and field testing, fieldwork started.

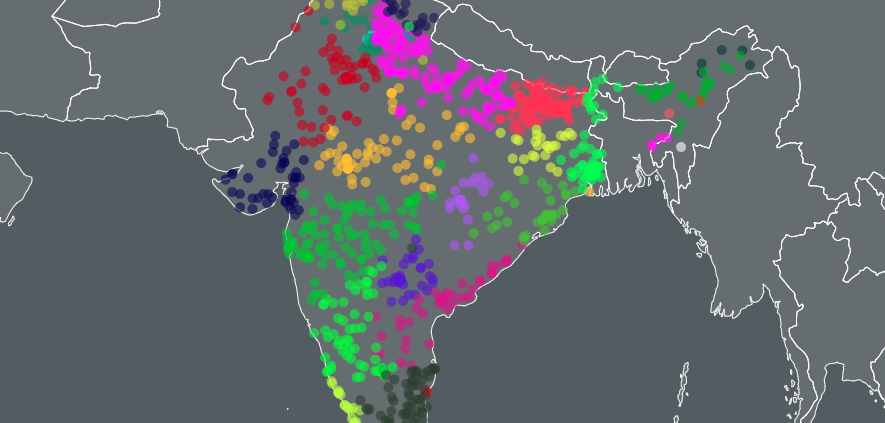

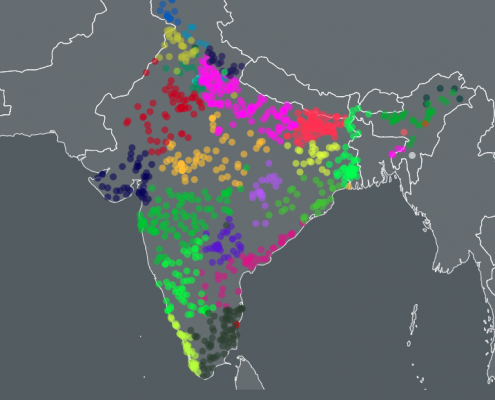

What a nationally representative sample looks like in India. Beautiful!

To my delight, fieldwork produced a genuinely national sample that includes Indian states proportionate to their contribution to the population as a whole, at only slightly greater cost. Some weighting was applied to balance demographics but nothing alarming. So, not only has CATI become a viable option in India, it’s actually preferable to the old way. Hey, thanks COVID!

Where Else Is the CATI Transition Happening?

Advances in mobile penetration have made a big difference in sampling complex countries like India, as well as in Indonesia and the South Pacific. In these countries, the distribution of respondents among hundreds of sparsely-populated islands make random sampling using F2F complicated and expensive. I have been doing CATI surveys for internal use with a client’s proprietary software in Bangladesh for the last few years, so I know it’s possible. Professional data collectors are doing so as well. Firms are also conducting promising experiments in Kenya and Nigeria. If you’re curious about other countries, contact me and I can look into options.

Lest my exuberance seem irrational, CATI is off the table in many places in Africa, Eurasia, Latin America and the Middle East. Because they exclude too many important voices, I resist the siren call of online panels, SMS and email surveys. Younger, urban and well-off respondents are easy to sample because they have access to these tools and are comfortable using them. However, such voices are already over-represented in debates over public policy. I won’t let COVID distort the debate even further by opting for samples that by design exclude the rural, the poor, the illiterate and those without adequate bandwidth.

Next week: Online qual: the Bad and the Ugly. Hopefully some good, too.